The 1869 issue of the United States was the world’s first pictorial stamp. Until that time all United States postage stamps, and all world postage stamps for that matter, depicted either heads of states or numerical figures. The 1869 issue was unpopular from the start. But it is important to note that deriding the quality and subject matter of United States stamps has long been an American pastime.

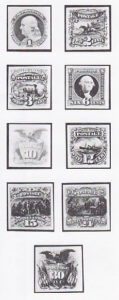

The one-cent buff (#112), with Benjamin Franklin’s picture, evoked praise for its execution but great criticism for its color, which is a dull buff. The color did not show the detail very well ad in its lightest shades is very difficult even to see. The two cent, in brown (#113), is a beautiful stamp that shows a man riding a horse. Equestrians from the beginning said that the designer of the stamp could never have ridden horses, and that no self-respecting horse would be caught with its legs in that position. The New York Herald said the scene looked like “[John Wilkes] Booth’s death ride into Maryland.” The beautiful three cent (#114) shows a locomotive, and is printed in an ultramarine shade that makes lovely copies rare. The six cent (#115) shows General Washington, and the ten cent (#116) in orange is exceedingly difficult to find in excellent condition. The twelve cent (#117) shows the ship Adriatic.

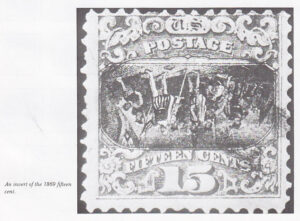

The high values of the 1869s begin with the fifteen cent. This was the first American stamp to be printed in two colors. Two-color printing using the line-engraved printing method is not easy. The stamps must be printed in two runs through the press, aligning the two colors, in this case making sure the vignette (or center) is balanced within the frame. Such centering of the printing is almost never perfect; the vignette always is off center in one direction or another. Surprisingly enough, stamp collectors who will drag a stamp’s price down for virtually any reason, real or imagined, do not pay attention to the centering of the vignette in a two-colored line-engraved stamp.

This fifteen-cent stamp shows a pictorial representation of the landing of Columbus. There are two types of the stamp, one (#119) with the center vignette framed by a line and a small diamond at the top (below the T of “POSTAGE”), and another unframed (#118). The stamp was originally printed without the diamond, and it is about twice as scarce that way. After a short while, the stamp department of the post office thought it would look better if the diamond took up what was considered to be an excess of white space around the vignette and this small change was made. The stamp with the diamond is known inverted—caused, of course, when one of the passes through the press was done improperly and the paper was turned around after one color had been printed and before the next. Then, as now, there were inspectors, but inspectors do not always catch everything they were supposed to. In philately, their mistakes make the hobby more interesting. It is odd, of course, that collectors value inverts so highly. Businessmen routinely throw away inverted letterheads, as do people who get an imperfect pad of checks from their bank. In stamps, such things are rarities. Though inverts are always called inverted centers, in some cases (like this one), they are really inverted frames. It depends on which was printed first, the vignette or the frame, and in the case of this stamp, the vignette was printed first. Only a few fifteen-cent inverts exist and they sell for thousands.