There are three major types of rarities in philately. There are errors-stamps like the Airmail Invert that were supposed to be one way but through printing mistakes came out another. Most are rare and, since most errors were known from the beginning of production, they are rarely found unidentified in collections. The second type of rarities are reissues or special printings-stamps that the Post Office produced for a special purpose and which you had to be in some way on the inside or at the right place at the right time in order to buy. Rarities in this category include the US Special Printings and Reissues that were produced for the 1876 Centennial Exposition and which exist in very small quantities. But the third class, the more egalitarian class of rarities, is what I call Production rarities.

Production rarities are stamps that were issued to the general public and could have been bought by anyone. They are rare because they were a little known denomination or issue or contain a variety or type that was consistent to all issued stamps of that type but different from the general issues. Because these stamps were issued generally and were not identified as distinct stamps by philatelists until later, it is in this class of rarities that “finds”, even at this late date, can still be made. Stamps like the #5, #482A (the 2c Type Ia imperf) and #314A were issued without fanfare and no collector could have bought them purposefully. Thus they exist in the stock of old letters and philatelic material that has been kicking around our hobby in junk boxes for years.

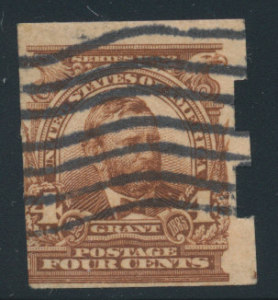

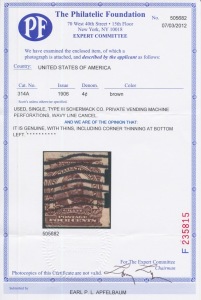

It was there I found the #314A picture above. Last summer at the APS convention I was looking at an auction lot, an old $300 estimate box, and I saw it. The characteristics of #314A are that it was a 4c Grant stamp of the 1901 issue that was ordered imperf by the Shermack company to be privately perforated for one of their customers who was sending out a mailer that required additional postage (thus the 4c rate). No philatelist knew of the stamp at the time and it has become one of US philately’s great rarities. This stamp looked right-the characteristic dark shade-and the cancellation was the correct one for the way that the stamp was used. And it was certainly ugly enough and damaged enough, which is how the genuine ones look, usually cut apart and carelessly handled. I bought the lot and sure enough the stamp was certified genuine by the Philatelic Foundation-the 32nd known copy and cataloging $50,000.