Political and social scientists study stamp issues for clues to how governments view their history and evolution as societies. United States stamp issues are replete with historical themes and make much of our founders. Benjamin Franklin, because of his role as our first Postmaster, is on nearly a hundred different US stamp designs, and Washington, Jefferson, and other Founding Fathers are not much behind. The values that America was founded on—unity, liberty and justice for all—have always been our national aspiration, even if attaining these goals has been more problematic. Other nations have more difficult relationships with their professed national goals and heroes, and nowhere is this more evident than with India.

The Great Man theory of history—to what extent do individuals influence historical events and to what extent they would have happened anyway—has been roundly debated by historians. Surely, America would have obtained independence from Great Britain had there never been George Washington. But equally clearly, genocide would not have been part of WWII to the same extent had there been no Hitler. India would have become independent of Britain had Mohandas Gandhi gone into his family’s business, not politics. But Gandhi attempted to change India in a way that many Indians were very resistant to. Gandhi believed in the equality of men, a concept that we Americans have been taught since childhood. India had no such tradition. The caste system and religious hatred among Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh had made for a system of highly stratified and systematized inequality. Gandhi didn’t just seek independence from Great Britain for his country; he wanted to change the basic fabric of Indian society.

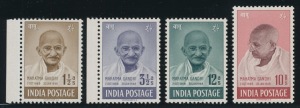

How well he succeeded is told by philately. Gandhi was on one of the first sets of stamps issued by India shortly after his death. After that, he received very little philatelic recognition—as if, proud of its founder, modern India has little time for his goals. Certainly, India is not the stratified society that it was a hundred years ago, but certainly there are mixed feelings on Gandhi’s message. 40% of students in India’s largest state (over 200 million residents) won’t eat lunches made at school because the school cafeterias employ untouchables. Caste issues have never been far from the surface in modern India. Gandhi’s near invisibility on the stamps of India quickly tell stamp collectors what social scientists study and try to evaluate—the goal of social harmony and equality in India is not a goal to which most Indians subscribe.