The lessons learned by Great Britain were not lost on America. This was a huge country, sprawling out by 1847 as far as California. The population density in the West was exceedingly low, although because of rich natural resources there were a good umber of small and medium-sized urban centers. The post office was required to serve all these small and medium towns, and, to complicate matters, the western states lobbied actively for cheap postage. In 1847, the United States government issued its first postage stamp, and at the same time reduced postage rates substantially.

The First United States Stamps

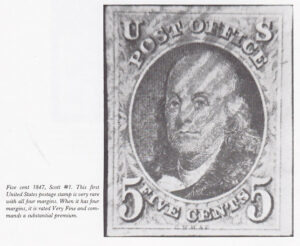

Collectors of United States stamps usually collect according to the numbering system of the Scott catalogue. The Scott catalogue numbers each stamp chronologically, beginning with the 1847 five-cent Franklin as number 1. Each stamp that is considered a major collecting type is given a number, or a number and a capital letter. Subtypes of each stamp are given a small alphabetical letter after the major number. Thus the brown shade of America’s first stamp is #1; the shade varieties that are variations of brown are called #1a, #1b, and #1c.

The first United States stamps were issued imperforate and were printed by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Edson, from stock dies held by the firm. The cost of line-engraving individual dies was great, and it was only natural that such double duty by the dies was used. The five-cent and ten-cent 1847 stamps were valid for postage on July 1, 1847, and were supposed to be in post offices that day. No first-day covers are known, and any covers cancelled during the entire month of July are very rare.

The five-cent 1847 stamp bears the portrait of Benjamin Franklin, the first Postmaster General of the United States. In terms of the quality of printing, though certainly not of design, this is probably the worst American stamp. The design was well chosen and properly engraved, but the impressing of the stamp onto the paper was usually poorly done. The high quality of the printing of the ten-cent 1847 attests to the expertise of the printers, so there must be other causes for the poor quality of the five cent. It has been theorized that the ink from which he five cent was printed severely corroded the plate. This theory would explain the general mottled impression that this stamp has. Strong, clear impressions command a substantial premium.

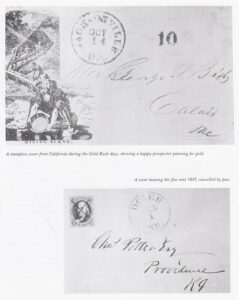

The five-cent stamp paid the regular first-class postage rate under 300 miles and the ten-cent paid the postage rate over 300 miles. Covers are known with both five-cent and ten-cent stamps on tem, generally paying for an overweight letter, but these are great rarities. Furthermore, five-cent and ten-cent 1847 stamps could be laced on letters posted from Canada. In this early period, senders could not mail prepaid letters across national boundaries, as each country wanted to collect the postage that was due for its part of the journey. However, some business firms in Canada with important American customers would pay the Canadian postage and put an American stamp on the letter to prevent the letter from going postage due. Such items are rare.

One area of concern for collectors who seek to acquire America’s first two stamps in mint, that is uncancelled, condition lies in danger of “cleaned” stamps. In this early period, most large post offices had canceling devices, but it was unclear to their postmasters whether they were to use the canceller to cancel the stamp or to use the machine to mark the date o the letter and then cancel the stamp by pen strokes. Small towns often had no canceling devices at all and pen and ink was readily used. A large percentage of the #1s and the #2s were cancelled by pen, and over the years some collectors, dealers, and just plain hucksters have “cleaned” the cancellation off the stamp. The details of cleaning are complex, involving the use of both heat and acids. The stamp appears to be unused, though of course it is not. And with unused five-cent and ten-cent 1847 tamps selling at fifteen times the used price, a buyer must exercise care. Most serious collectors and all competent professionals can tell a cleaned stamp from an original, unused one. Under high magnification the pen mark can never be completely eradicated. Still, it would be wise to insist on a certificate of authenticity (see page 73) before buying a unused 1847 stamp.

But this is largely academic because most collectors collect these first two stamps used. The deep rich color of the stamps lends itself well to canceling, red cancellations being the most common. Most collectors of United States stamps collect used stamps to 1890 and unused after that, though this is often an economic imperative rather than an aesthetic choice. Unused stamps before the 1890 are prohibitively expensive.

Prices of the United States’ first too stamps have been rising steeply, quadrupling in the decade of the 1970s.