The 1857 Issue

Great Britain began perforating its general issue postage stamps some two years before the United States. In 1857, the Post Office Department contacted Toppan, Carpenter & Company (the printers of the stamps, and the surviving firm from Toppan, Carpenter, Casilear & Company, printers of the 1851 issue), and instructed them to begin planning to perforate the stamps. Ease of separation was cited as the reason, but it was also believed that perforated edges would make the stamps adhere better to the letters. Toppan, Carpenter & Company, with but four months left on the six-year contract they held to produce these stamps, was quite reluctant to go to all this additional expense with so little time remaining. A compromise was worked out whereby the government paid for the cost of the new perforating equipment, which would then become government property if the contract was not renewed. The perforation of the 1857s measures perf 15.

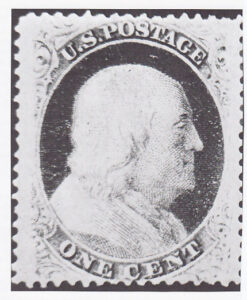

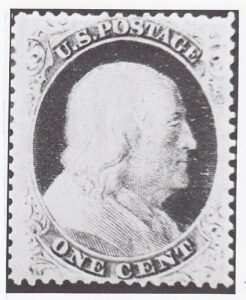

The One Cent 1857

The types of the perforated stamps are the same as those of the imperforate stamp. However, because new plates were prepared and used in addition to the original plate, Type I and IA, which are so very rare imperforate, are relatively more common on the perforated plate. This has led to some trickery, as certain collectors will trim the perforations off a #18 in an attempt to make it look like a #5. fortunately, a dot n the circle around the portrait of Franklin at 8:00 was added to the later plate, making it impossible to fool knowledgeable philatelists.

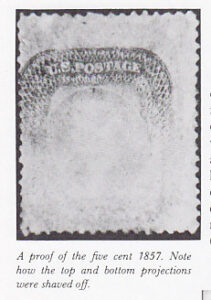

And the original #5 ha a characteristic double transfer (a doubling of the design due to fault entry of the die onto the plate) not found on any of the perforated Type Is. Part way into the press run of the perforated stamps, a change was instituted. The stamps were aligned so closely together on the original plate that when perforations were placed between the stamps, they often cut far into the stamp design, and the post office complained.

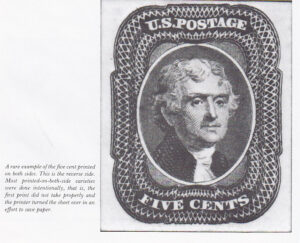

We should realize that the printers of these stamps were not in fact aware that there were subtle differences in the stamps they were printing, and probably would not have cared very much if they had known. After all, they were under contract, with set delivery dates, to produce the postage stamps for a nation. The decisions that they made as to sheet size, spacing, and printing were purely utilitarian ones, dictated by concerns of cost and efficiency.

It is obvious, then, that when the one cent Type V was created, it was not done with the intent of confusing later philatelists. But as the perforations cut too far into the design, the post office objected, and when you are in business as Toppan, Carpenter was, and your client complains, you take steps to remedy the complaint. Accordingly, part of the design of the stamp was burnished (removed by scraping the steel on the plate) away on all sides, so that the stamp resembled Type III at the top, but it also missing quite a bit of design at the sides, which never happened in Type III. This is the Type V, known only on the perforated stamps.

Quality on the one cent 1857 perforated stamps is nearly always a problem. The entire 1857 issue is not graded as strictly as are the other United States stamps. There was simply no room to place the perforations except on part of the stamps, so collectors must expect that even Very Fine or better specimens show portions of their designs with some perforation holes. The Type V (#24) is the exception to this rule—it was created solely to make more room, and spectacular examples are occasionally found. In ascending order of scarcity, this issue is listed #24, 20, 22, 23, 18, 21, 19, with the #19 approximately seventy-five times more scarce than the #24.

The three-cent 1857 stamp is the same as the three cent 1851 with the addition of perforations. While there are two types of three-cent 1851 stamps (#10 ad #11), these two types are distinguishable by shade alone. The two types of the three-cent 1857 stamps are distinguished in that after perforating some of the #11s, the frameline of the horizontal rows between the stamps were removed to make more room between the stamps for the perforation holes. Thus the Type I #25 has a frameline above and below the stamp, while the Type II # 26 does not.

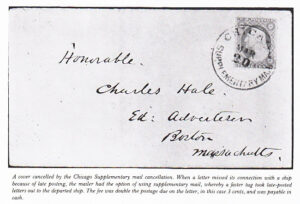

The #25 is about ten times more scarce than the #26. The #26 was the stamp that carried the bulk of the mail posted in this country during the years 1857 to 1861, and is the most common stamp in the 1857 series. In 1980, the stamp customarily traded at about the $1.50 level for an ordinary used example; unused versions began at about $30. Because of its relative accessibility, many collectors have specialized collections containing thousands of copies of this stamp. Often the stamp was found with what philatelists call a circular date stamp cancellation—a cancel containing the town name and the month and the day. Some collectors try to make what is called a “calendar collection”—a collection of 366 stamps cancelled for each day of the year. Theoretically, nod ate should be scarcer than any other except for February 29, of which there should be one-fourth as many. But completing a “calendar collection” usually requires searching through tens of thousands of stamps.

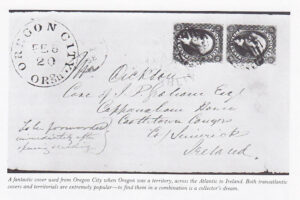

The years of this issue, 1857 to 1861, were an exciting era for America, and this is reflected philatelically. It was a period of western expansion, and collectors often seek cancellations from small western towns. Te railroad was an active mail carrier, so collectors look for distinctive railway post office cancellations. So too, with steamboats on the Mississippi, gold and silver mines, and cavalry troops fighting the Indians—all of these bits of history produced letters, and all of them have distinctive cancellations known to and collected by philatelists.

And there was the Pony Express. Born in the hopes of rapid communication between the East and West Coast, the Pony Express riders set out from St. Joseph, Missouri, across Nebraska, over the Sierra Madres to California. Every 15 miles or so along the route a change station was built so that riders would always have fresh mounts. Here, horses were kept with the station master, and were saddled and made ready as the rider approached. The exchange of horses was a marvel of efficiency, with the rider hopping off one and onto another in a flash. Each rider traveled about 75 miles in a given ride, or about five or six exchanges, resting at the farthest exchange station before beginning a ride back.

The Pony Express could deliver a letter across the continent in ten days. But it was only in existence eighteen months, by which time the coincidence of the Civil War and the laying of the transcontinental telegraph forced this fascinating private post out of business.