The British Post Office had evidence that some postal users were clipping uncancelled parts of stamps and reassembling them on letters to pay postage. Finally, in 1857, the post office got around to ordering stamps with four check letters, the letters in an order reversed from the top to the bottom. The check letters make it much more difficult to use uncancelled portions of stamps convincingly.

The One Penny 1864 with fourcorner check letters is one of the most popular specialty stamps in the world. Many collectors who do not even collect general issues of Great Britain maintain a holding of this stamp. It is about the easiest stamp in the world to plate, for not only do the check letters tell a collector the position of the stamp, but in the tablets at the right and the left of Queen Victoria’s head are engraved the plate number of the plate that the stamp came from. One hundred fifty plates of this stamp were used over its long life, and with the exception of the last plate, plate, plate 225 (which was only in use for four weeks), none of them is particularly scarce, except for plate 77. Plate 77 was rejected as defective, but a few examples have surfaced. Edward Bacon, one of the printers, believed that these very rare plate 77s were trial printings from the plate, made before it was destroyed. A few of these trials somehow managed to get out to post offices and be sold to postal patrons. Examples of plate 77 are among the major rarities of worldwide philately. Many hearts have stopped beating when a collector confused a plate 177– a very common plate– in which the “1” was obliterated by the cancellation, with a plate 77.

With some 150 plates and 240 stamps in each plate, a collector would need 36,000 different examples of the same stamp in order to complete a plating and positioning of this stamp (though only 240 are need for a positioning alone). Until recently, in quantities the stamp sold for less than 1 penny a piece. Now they probably sell for about 15 cents. There were over 30 billion printed during the life of the stamp. Although statistics of this kind are difficult to correlate, this is probably the largest printing of a nineteenth-century postage stamp, and may well be the largest printing of any stamp ever.

The very quality of the line engraving by Perkins, Bacon & Petch, which proved to be such an effective anticounterfeiting device, also greatly concerned the Post Office Department. It was felt that the line-engraved stamps could withstand a veritable bath of ink eradicators and the design would still be as clear as ever. The department was very concerned over this potential (mostly imagined) cleaning and reuse. It therefore instructed another printing company, the De La Rue Company, to begin printing a four-pence stamp typographed, that is surface-printed, with a somewhat fugitive ink. Anyone attempting to take a cancellation off one of these surface printed stamps would soon find himself with the design leaving the stamp before the cancellation did. The first surface-printed British stamp was issued in 1855; it continued in use, with some watermark changes, until 1862, when a new issue was called for.

The 1862 issue was also a surface-printed one and incorporated a 3-pence, 6-pence, 9-pence, and 1-shilling value, as well as a revised 4-pence of the previous issue. The reason for the revision on the surface-printed stamps was the same as it was on the engraved, that is, to place corner check letters in the four corners so as to prevent a patron from clipping two uncancelled halves from used stamps and pasting them together on an envelope, thus defrauding the government out of revenue. The surface-printed issue with small corner letter are extremely attractive and well-designed stamps. Their colors were well chosen and they have retained much of their freshness even until our day. The nine pence is an especially scarce and undervalued stamp. It was used to pay the postage on prepaid letters to India, Australia, and South America. Undamaged covers bearing well-centered stamps are very scarce, and because of the remote destinations and lack of stamp collectors in the non-European continents, few of the nine pence were saved. It is an excellent stamp. Like all the nineteenth-century Great Britains, the nine pence is exceptionally difficult to find well centered; and well-centered, mint, original gum examples are a combination that is seldom seen.

In 1865, the same set was reprinted on the same watermarked paper (small emblems in each of the four corners of the stamp), but this time around the corner check letters were greatly enlarged because it was felt that the tiny letters on the previous issue did not especially discourage cutting and ruse. Again a 3-pence, 4-pence, 6-pence, and 1-shilling value were issued. However, a great rarity, a ten pence on emblem-watermarked paper, was also inadvertently issued, when the next set, the 1867 set, was printed, and is actually an error. It is a later stamp accidentally printed on an old batch of paper.

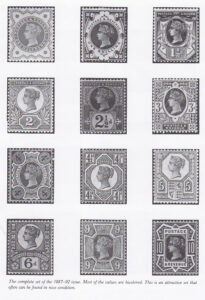

The 1867 set was basically the same group of stamps printed on a paper with a new watermark– a pattern that looks like a rose. A number of values were issued over the next thirteen years and these are among the most interesting tamps of the British Commonwealth.

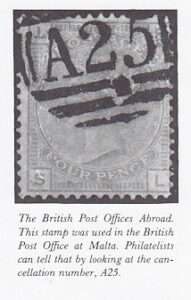

For decades, throughout the nineteenth and well into the early twentieth centuries, the British operated post offices in all corners of the world. These were different from the post offices that their colonial governments ran, which issued their own stamps and provided internal postal service for the countries involved. Rather, the British Post Offices Abroad, as they were called, were far-flung extensions of the British Postal System. They used Great Britain stamps, and operated as a British Post Office in such places as Chile, Peru, and Thailand. British postal officials cancelled British stamps used there with distinctive cancellations, usually bearing a letter followed by two digits. Thus, A26 is Gibraltar and C51 is St. Thomas. The internal post offices mostly used three-digit cancels with no letter. In all, there were hundreds of British Post Offices Abroad cancellations. Often letters are seen bearing both the postage of the country where the British Post Office abroad was, so as to pay carriage to the British Post Office, and the British postage, to pay the British carriage. Used Abroads are a fascinating specialty, and indeed the use of British stamps abroad was so widespread that most stamps thus used sell for only a modest premium over a regular usage. Covers are a different story and can command substantial premiums.

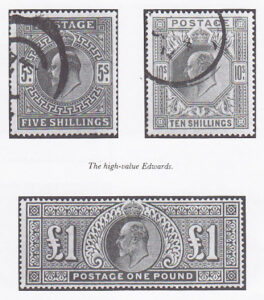

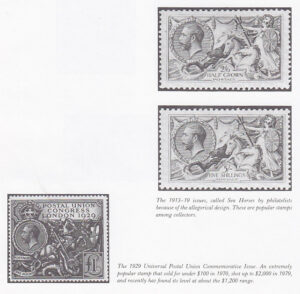

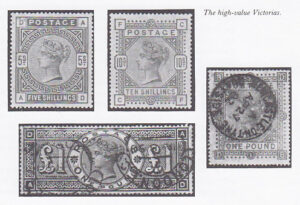

In 1867, Britain began issuing a series of high values that would give it by 1882 the highest face value stamps in the world. In that year a five-shilling stamp was issued which had a face value of 5 shillings (at that time approximately $1.30). The United States had issued several ninety-cent stamps, so this British high value was not unprecedented. Indeed, one Liverpool firm complained that it frequently sent postal packets requiring postage of 70 shillings and the firm complained that the package was so full of stamps there was no room for the address. The five shilling came out in 1867; a ten-shilling and one-pound stamp both in 1878. In 1882, a five-shilling, ten-shilling, and one-pound stamp, all with a different watermark, came out, as did one of the highest value stamps ever issued, a five-pound stamp with an astonishing $26 face value. In 1882, that was a great sum of money. The Five Pound stamp remained in use until 1903, and during its life about a quarter of a million were printed and sold. An odd fact of life about very high value stamps is that a much large proportion of them are saved than of the used lower-value stamps. They were a curiosity rarely seen by people when they were used, and so were rucked away by even noncollectors.

The stamps of Great Britain are a complex field, assembled by collectors in Great Britain to a degree of specialization that this chapter can only begin to suggest. In particular, English collectors love to classify minor varieties of shade. Indeed, rarely do Americans or Canadians seek out anything but the most striking of shade varieties, whereas the British find eminently collectable the minor variations of shade that occur even between different printings of the same stamps.

British stamps are a wonderful specialty, worthy of an inquisitive, inquiring collector at any stage.