The D grill measures 12 by 14 millimeters, or fifteen rows or points by seventeen to eighteen rows (the reason that the number of rows sometimes varies within a grill is that they were set only approximately o the grilling machine, so there are slight differences). It is known on two stamps, the two-cent Blackjack (#84) and the three cent (#85). The numbers issued are 200,000 and 500,000 respectively, so that a fair evaluation of the number surviving in collectable condition would be perhaps between 2,000 and 5,000 of each.

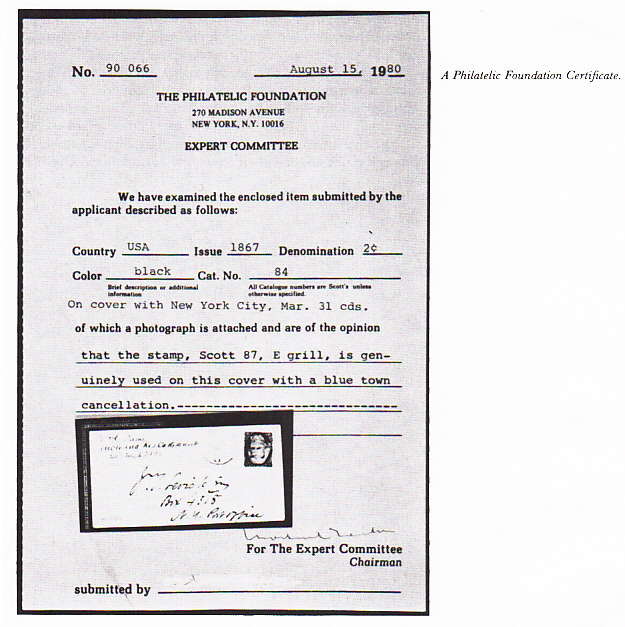

The E grill is the second most common grill, measuring eleven by thirteen millimeters (or fourteen by fifteen to seventeen points), and is found on the one cent (#86), two cent (#87), three cent (#88), ten cent (#89), twelve cent (#90), and fifteen cent (#91). Though all E grills are scarcer than the stamps without grill (the 1861 issue), they are not rare. The